Less Is More: An Agent's Case for Cutting the Clutter

Tighter prose, stronger voice, bigger impact

Every week, I receive dozens of queries where talented authors bury brilliant ideas under superfluous words, believing more words equal more impact, style or literary weight.

Most often, more words are usually… just more words.

I’ve found the most enjoyable manuscripts are ones where every word earns its place. This is not a call for "plain" writing, but rather purposeful writing.

The Clutter Epidemic

William Zinsser saw this coming decades ago. In On Writing Well, he declared, "Clutter is the disease of American writing." He notes, “The secret to good writing is to strip every sentence to its cleanest components. Every word that serves no function, every long word that could be a short word, every adverb that carries the same meaning that's already in the verb…"

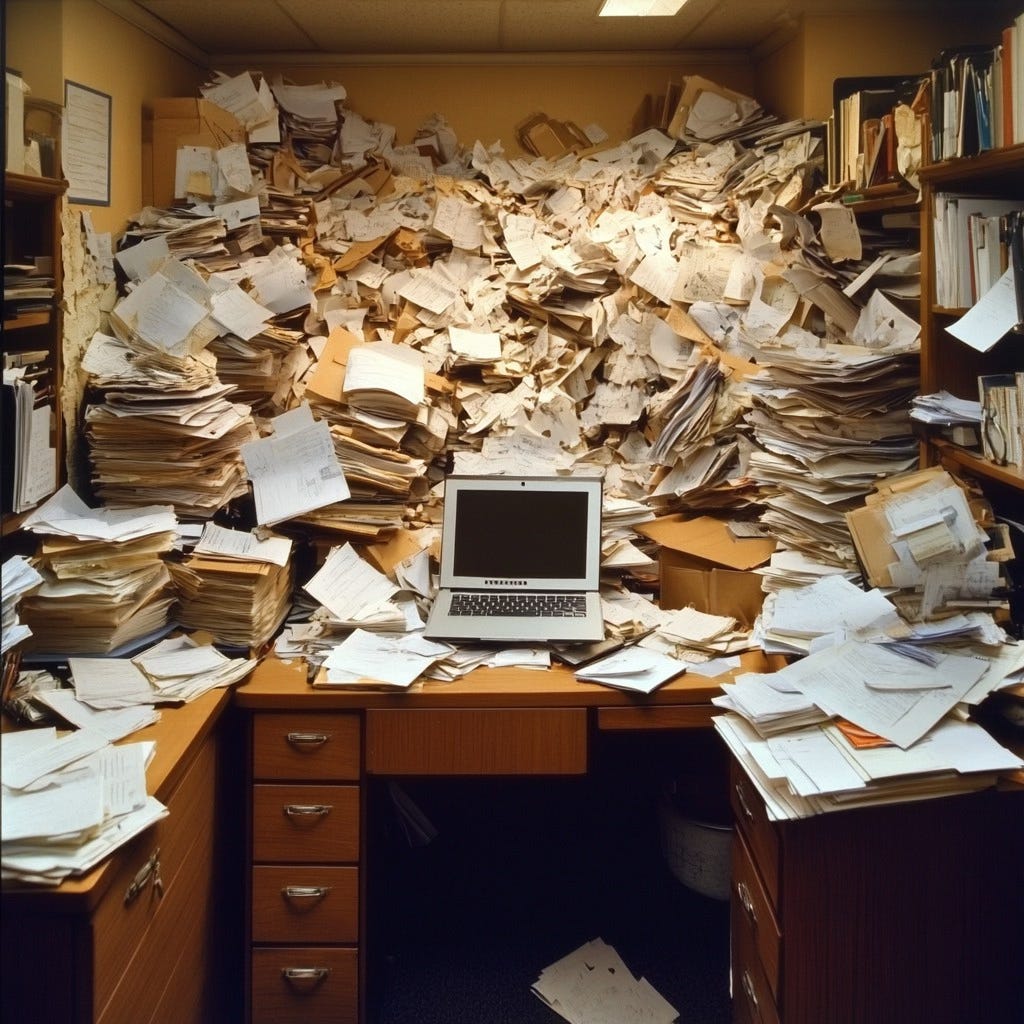

I hadn't read Zinsser until recently, and was thrilled to find corroboration for what I tell writers who accumulate phrases the way I accumulate notebooks: cut down on the unproductive verbiage. Extra words often create meandering narratives.

Many editors resist trimming, fearing it impinges on the writer’s style or voice. But voice isn't clutter. Voice is what remains after you've cut what doesn't advance the story. This isn’t to say your prose can’t be lush, but it should always serve the narrative.

Whereas style is measured more by the precision in which words are used, than by their quantity. Joan Didion didn't write The Year of Magical Thinking by accident. Every sentence was honed, every phrase deliberate. Her voice comes through because of economy, not despite it.

If a reader—or an agent—has to wade through unproductive sentences to understand what’s happening, the style isn’t landing, it’s laboring—and I’m willing to bet the pace is too.

Style vs. Excess

Let me show you an example I see often:

The rain, in all its dreary persistence, fell relentlessly from the heavy, ominous sky, creating an almost impenetrable curtain of shimmering droplets that danced and collided in chaotic patterns upon the already sodden pavement, where shallow pools reflected the fractured light of flickering streetlamps.

I can already hear the dissenters: “But it’s literary—it sets the scene and tone” Setting the scene is fine, but how long do we have to stand here before the story starts moving? You might as well reduce it to “It was a dark and stormy night”…

In the end, it’s a long way to say it’s raining. I’m also willing to bet what happens next doesn’t happen because it’s raining.

Linger too long on minutiae, and you’re not deepening the scene—you’re bloating the word count and dragging the pace.

Have confidence in your story. When you trust your plot, characters, and themes are strong enough to carry the narrative, you don't need to dress them up in elaborate language.

The Revision Process

I often counsel writers to approach revision like a sculpture. Michelangelo didn't add marble to create David—he chipped away everything that wasn't him. Your job is similar: remove the fluff detracting from your story.

Start with adverbs. Most can go. If you need an adverb, your verb isn't strong enough. "She ran quickly" becomes "She sprinted." "He spoke angrily" becomes "He snapped."

Look at adjectives next. Do you need "tall, imposing oak trees" or would "oaks" work? Often, the noun carries the weight you're trying to add with description.

Watch for redundancy. Don’t say “he nodded his head” (what else would he nod?), “she shrugged her shoulders,” or “he blinked his eyes.” These extra words aren’t necessary. Trust the reader to fill in what’s obvious.

Finally, examine sentence structure. Academic writing trains us to be thorough, to qualify every statement. Fiction demands the opposite. Be bold. Make claims. Trust your reader.

Sometimes More Is Less

Concise writing isn’t the enemy of style. Remove the clutter and your voice remains—clearer, stronger, more distinct. That’s not dilution, it’s distillation.

Your job isn't to impress with how many words you know. It’s to move readers, make them think, and keep them turning pages. Clearing the clutter is a solid first step.

Further Reading

Scene Setting or Inventory List: Excessive Description

This makes me think of Raymond Carver short stories. Every word feels like a carefully placed brick.

I often see something similar on organizations' websites, especially nonprofits. They'll say, "Our 501c3 utilizes best practices to build bridges between civic partners and those on the front lines fighting to distribute nutritionally balanced, satiating meals among individuals experiencing food insecurity," when what they mean is "We serve hot meals to hungry people."